SAMPLE THE BOOK

In the matter of mould

I have written about mould previously. You may recall The White Mould of Happiness and the evil Mould of Many Colours. Feiner, in his very excellent technical treatise, “Salami” embarked on a much more esoteric analysis. Mould and sometimes yeasts are applied to sausages which are to be air dried. He opined that, in terms of the mould applied, members of the genus Penicillium are frequently chosen to inoculate salami. In terms of the yeast used, members of the genus Debaryomces are occasionally applied. These inoculants are chosen because they are salt tolerant and do not reduce nitrate to nitrite.

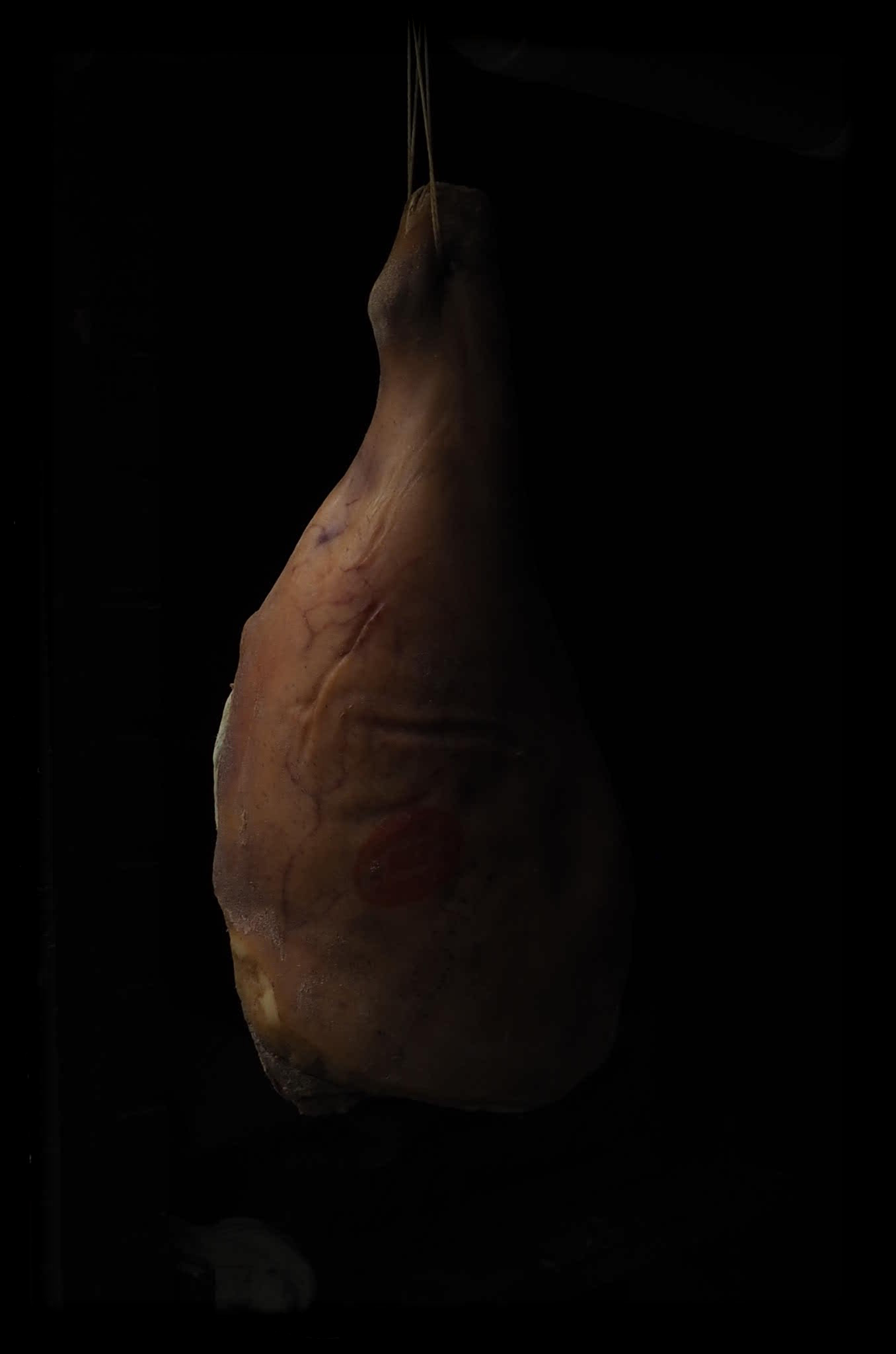

Further, Feiner opined as to the attributes of moulds as follows. Mould on the surface of salami keeps away oxygen and therefore stabilises curing colour inside the salami. Mould also contributes to the development of the typical salami flavour as it contains proteases and lipases which break down proteins and fats into components such as amino and fatty acids. In addition, the learner author informed us, the presence of the layer of mould on the surface slows down development of rancidity as it protects the salami from the impact of oxygen, and light. The layer of mold also slows down the loss in weight during drying of the product and minimises the risk of obtaining case hardening.

Interestingly, he observed that yeast requires oxygen for growth and only grows on the surface of a salami. Also even slight treatment with smoke kills the yeast present on the surface because yeast cannot tolerate certain components in smoke such as phenols and organic acids

Feiner also observed that what he described as “noble mould” (The White Mould of Happiness) is white or grey/white in colour and unwanted moulds (The Moulds of Many Colours) can display a wide range of colours and are often black, green or even yellowish.

He explained that the major cause of growth of unwanted mould is having a high level of humidity for too long at the beginning of the fermentation stage and/or the application of smoke too late in the production process. If these conditions occur generally mould starts to grow and salami after around three or four days during the initial stage of fermentation. Airflow also has an impact on mold growth and if airflow is too slow mould growth increases. Growth of mould also occurs during drying of products, once again usually because the humidity is too high in the air velocity is too low. Further, he stated, drying room should be free of mould given that the mould in the chamber would inoculate mould free products and exacerbate any problems.

Feiner observed that the parameters in which unwanted moulds are encouraged are at humidity levels above 75% together with warm temperatures and low air velocity both of work which speed up growth of mould.

Further, despite being unattractive to the eye and producing a bad smell, a few species of unwanted mould produce different mycotoxins, Feiner informed, which penetrate the product. Therefore, the removal of unwanted mould from the surface of the salami only removes the visible part of the mould; the mycotoxins is still present inside the salami further proteolytic mould can also cause a sausage casing to deteriorate entirely. This is indicated by black spots seen on the surface of the salami just under the casing.

Moulds can be acquired from commercial suppliers for the purposes of inoculating salami. This is usually done by dissolving the mould, which is a powdery substance, in some distilled water and then spraying it on the exterior of the sausage with a misting bottle. Alternatively, another way to inoculate mould is to use the mould which you have found naturally occurring on your air-dried products. Wait until it is dry and then brush it from the surface of the sausage and push it through a sieve to break up any small clumps. This can be kept in the freezer until desired and applied in the fashion of a commercial mould.

On fermentation

Fermentation is a technique often applied in air dried sausage production. I avoided it in the first book because I was scared of it. I still am to some degree, but my fear is manageable. The reason for my apprehension was because it involves allowing the sausage, once in the casing, to stay at ambient temperature and humidity for about 48 hours. The purpose of that is to encourage fermentation of the meat. This seemed to me to be an inherently risky step and a bridge too far when embarking on the daunting process of making charcuterie. It was for that reason that I did not embrace meat fermentation as a step which I needed to take. Indeed, it is not a step which one needs to take but it is a step which one can take if one is brave enough. Marianski in “The art of making fermented sausages”, broadly described the process as follows “Meat fermentation is accomplished by lactic bacteria, either naturally present in meat or added as starter cultures. These bacteria feed on sugars and produce lactic acid and small amounts of other components. Increased amount of lactic acid results in higher acidity (lower pH) which not only creates a highly desirable product, but also prevents the growth of spoilage and pathogenic bacteria”. The last part of the explanation did have some resonance with me but I was still scared.

In the warm domestic environment (20°C – 22°C), fermentation occurs and all the bacteria in the sausage are encouraged to grow. However, the bacteria which produced lactic acid multiply quite readily in these salty and low water level conditions whereas the pathogenic bacteria, particularly if nitrates are used, do not. This is a good thing.

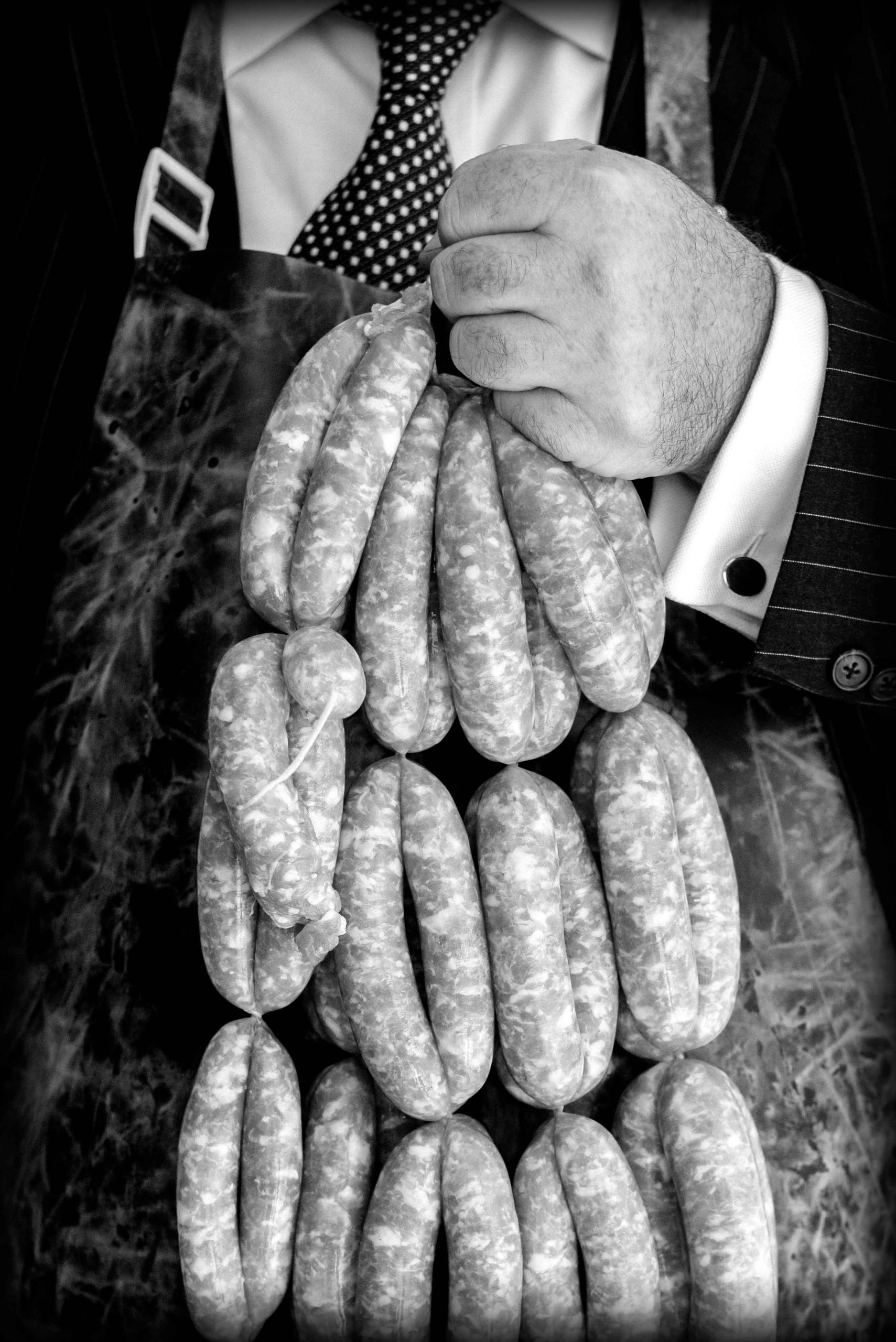

The fermentation process is accelerated by temperature, however for domestic purposes ambient temperatures of, say 22°C ,are sufficient for the process to commence. A reasonable atmospheric humidity is also required but this will naturally occur inside your home unless you live in an especially dry and hot place. In Melbourne during winter but also during summer (unless really hot) I have found that the ambient temperature and humidity inside my house is about 22°C and approximately 80% relative humidity. I hang the sausages in the laundry which is neither too hot nor too cold and leave them for approximately 48 hours. You will observe that the exterior of the sausage dries out somewhat, that is to be expected. You will also observe the colour of the sausage becomes much redder, to an almost ruby red. This is also a function of the fermentation process. The resultant product once the air drying has been completed as a slightly sour taste which is characteristic of air-dried sausages. That is the indicator of the presence of lactic acid.

I have been including fermentation as a step, in air-dried sausage production, for some time now. To my knowledge there have been no fatalities and no debilitating personal injuries.

For the technically inclined, and I know there will be at least one amongst you, I refer you to Marianski “ The art of making fermented sausages” and to Feiner’s excellent work “Salami- practical science and processing technology”. The latter is from an Australian point of view and traverses the physiology of meat as well as its biochemistry.

Air-dried duck sausage with figs and hazelnuts

| This is an air-dried sausage based predominantly on duck meat. It is a variation on another recipe using rabbit and hazelnuts. It is a very nice air-dried sausage and I encourage you to give it a try. | ||

| Ingredients | Method | |

| Duck (breast meat minced or finely diced) – 50%

Pork (minced shoulder) – 50% Pork (back fat, finely diced) – 20% Salt – 3% Curing salt No 2 – 0.3% Dextrose – 0.5% Sugar – 1% Pepper (black, cracked) – 0.1% Pepper (white, ground) – 0.1% Garlic (powder) – 0.2% Onion (powder) – 0.2% Thyme (dried) – 0.1% Tarragon (dried) – 0.1% Juniper (Berry, crushed) – 2 Fig (dried, finely diced) – 0.04% |

Combine the duck meat (skinless and fat removed) and the pork mince with the salt. Add minced figs. Mix well. Refrigerate overnight.

On the following day combine all the remaining ingredients and mix well until a sticky consistency achieved. Pipe into 35 mm – 40 mm casings. Ferment at room temperature for 48 hours. Air-dry until at least 40% weight loss is achieved. Note: When using game meats to make air dried sausages remember that the meat is lean and tends to shrink more than fatty minced pork. There are two consequences of this. First, the diameter of the final sausage will be a lot less than the original diameter. Secondly, and more importantly, the diced back fat does not shrink to any significant degree. Accordingly, it can result in a cross-section of the end product with the back fat being disproportionately large. It seems to me there are two ways to overcome this problem. First, dice the back fat as finely as you can. I suggest one quarter fingernail sized. Secondly you can consider reducing the amount of back fat to, say, 10%. That would be fine with this recipe because it has added minced pork. However, for recipes which do not have added minced pork try reducing the back fat to 15%. It is a matter of preference. PS. Figs can be hand cut and added but they dry unevenly. Minced is better. |

|

Squid ink salami

| This is a recipe for the brave. The squid ink and the distinctive colour firstly, but not a fishy taste as one might expect. The resultant texture can be somewhat soft, but it is worth a try. I know you can do this. | ||

| Ingredients | Method | |

| Pork (minced, 50% shoulder and 50% belly) – 70%

Pork (back fat, hand cut at about half fingernail size) – 30% Salt – 2.5% Curing Salt No. 2 – 0.25% Garlic (powder) – 0.3% Pepper (black or white, powder) – 0.3% Dextrose – 0.2% Milk powder – 2% Cuttlefish ink – 1% Chilli (dried flake) – 0.3% |

Mix all ingredients except diced back fat and cuttlefish ink. Refrigerate overnight in a covered non-reactive container.

On the following day, mix well until the mixture is sticky. Add cuttlefish ink. Depending upon the meat and herb mixture, some additional ink may be required to achieve a good black colour. Once the colour saturation is achieved satisfactorily add the diced back fat. Fill using 30 mm – 40 mm casings. Allow to ferment at room temperature for approximately 24 hours. Air dry at approximately 12°C – 14°C and at between 60% – 80% relative humidity until a weight loss of at least 30% is achieved. The squid ink tends to make the product somewhat softer than one might expect. It may require further air drying to achieve a texture which is satisfactory. |

|